In the La Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve Zone, on the border zone between Colombia and Ecuador, Jani Rita Silva Rengifo tries to heal the 'open wounds' left on the wetlands and in the forest by oil exploitation, pollution and the opening up of a road in Puerto Asís, Putumayo.

If Colombia were a woman's body, the La Perla Amazónica region in Putumayo would be her underbelly. There, part of the ecosystem is the river that bears the name of the department. Like a snake, it twists and turns, draining a basin of 148,000 square kilometers that includes 1,813 kilometers of waterways. The river also forms a natural border with Ecuador, a neighboring country to the south of Colombia, and its force advances and crosses the frontier into Peru and Brazil.

An aerial view would show it is a nerve of the planet, one whose brown waters flow into a middle branch of the majestic Amazon River. The branches of the Putumayo River in this part of the continent are the canals and waterways that care for and sustain life for Jani Rita Silva Rengifo and the inhabitants of 23 rural communities in the area. But the road that leads from Puerto Asis to La Rosa, passing through approximately five thousand hectares of territory, is an open wound carved out by oil companies in that belly of water. Rather than being treated as a sacred place, it accumulates the black scars oil exploration leaves swollen on the ground.

— I am more threatened by the issue of the road than anything else. I would ask you to be careful with things. I can tell you how they are, but I would ask you to be very careful, insists Jani.

— Why do you threaten them?

— We began to raise environmental issues with the oil company, and that's when the threats started.

At age 57, Jani has seen it all from that powerful womb of Colombia. Yet, the pandemic took her by surprise. She didn’t see it coming. Mandatory confinement forced her to remain in quarantine for several months and at the mercy of those who threaten her. All of a sudden, she and the peasant farmers and local inhabitants who are part of the Association for Sustainable Integral Development of the Amazon (ADISPA) - which works to ensure environmental sustainability in the region - were separated until July 2, when they noticed a spill of 3,000 liters of fuel oil; that is, diesel, in Platform 1 of the Platanillo Block. In fact, the Platanillo Block is reason for the scar left by construction of the road.

When peasants from the communities of La Alea, Peneya and Bajo Mansoyá reached the area affected by the spill, they saw dozens of dead fish. The diesel spilled into La Sevilla, a creek that flows a few hundred meters downstream into the Mansoyá River. The spill was verified by a committee comprised of representatives from the oil company, Corpoamazonia, ADISPA, the community action boards of the aforementioned communities, and the Intefaith Commission for Justice and Peace.

The verification committee reminded Amerisur Resources, the British company that apparently still operates oil wells in Putumayo, that the minimum distance between Platform 1 and the river should be 100 meters, not "27.57 meters" as in this case, which constitutes an environmental infraction. Had that rule been observed, the spill would not have reached the water. The structure that overflowed with diesel could have been monitored and shut down in time, because it operates with a lever that is activated manually. "There is no preliminary information for an initial diagnosis of affected species, information that should have been part of environmental impact assessment conducted before the platform was set up," states the report, which was written by hand and almost in streaming; that is, in real time, by the farmers, men and women who are members of ADISPA and, along with Jani, are watchful of their territory. They also made the company see the spill was affecting the human right to water in the nearby communities, and asked how the damage was going to be repaired.

The community has achieved this technical level of environmental scrutiny due to past accidents. Learning these rivers and the Amazon rainforest belong to them has been a two-decade long process in which they have come to understand they must be vigilant. If not, the government in its blindness and from its base of operations in Bogota, the capital of Colombia, will not do it for them, at least not with the level of expertise they have on the ground. It´s a simple matter: no one is hurt more than them by the scars left by oil exploration and production. The local community has devised a sustainable development plan that has been improved over time, one they are using to monitor the oil company “drop by drop”.

For a few seconds, you can sense the anguish in Jani’s voice. Later, this feeling turns into fatigue. She knows if she doesn't tell the story as many times as necessary, she will forget. And, no. She cannot allow that to happen, especially now. So, she takes a deep breath and continues our interview.

— The development plan was put together by us, with our own resources and support from the government. We have updated it with some international cooperation, but very little, like eight million pesos. For us, updating [this plan] is like an exercise in life. It shows how much we care about the land and how we want to live. On the other hand, the environmental development plan presented by the company was purchased from an operator who drafted it without considering what we have here, since they are the intruders.

The community’s document on territorial and environmental order does not contemplate further drilling and extraction of oil in the region. However, those who live in the Peasant Reserve Zone (ZRC) did not expect Amerisur to be acquired last year by GeoPark, a British company, at a cost of 42 million euros. The purchase was announced publically on 15 November 2019 in an executive summary that stated: "The acquisition of Amerisur is in line with GeoPark's strategy of continuous expansion, which aims to achieve the long-term goal of producing 100,000 BOPD [barrels of oil per day] and even more.” GeoPark came in strong and announced it will "incorporate twelve oil production, development and exploration blocks" in the country, and eleven of them will operate in the Putumayo basin.

As mentioned on the Crudo Transparente website, the National Mining Agency (ANH, by the Spanish acronym) reported the Platanillo Block produced 1,369,440 barrels of oil in 2019. The same source also pointed out that 451.980 barrels were extracted there in May 2020, which is less than usual because of the effect the pandemic has had on the world market for oil.

— Oil production did not stop. Are there any cases of COVID in the Peasant Reserve Zone? I ask Jani.

— It´s the same old thing. There are villages located within the oil sector where people have been infected with the virus because they work directly on the platforms. They say the first one to infect the others was someone who went to the other platform with a mule driver who had the disease, and it seems he infected more than one person. We were told the company did not want to go into quarantine. So, what it did was to send the sick man home. It’s an irresponsible act. What is very clear is that people have tested positive for COVID and there are still some who are infected with the virus.

She also says those who work at Platanillo returned to their homes in the villages in sectors 1 and 4 of the PRZ, which includes the stretch of road between Puerto Asís and La Rosa. This is a border zone where people pass directly into Ecuador, through El Palmar. According to the National Institute of Health, 3,401 cases of COVID-19 and 154 deaths from the virus were reported in Putumayo. In 64 percent of these cases, the virus was dealt with at home.

Be that as it may, everything seems to indicate the scar left by this roadway was the path the disease took to reach the peasants in the reserve zone. Although Jani knew of a peasant woman who died from respiratory complications, and told the community about her death from the virus, she is still not sure about the number of fatalities.

Jani is not a native of Putumayo, and when she arrived it was already late in the game. The Texas Petroleum Company began operating in the area very early on, in 1942. However, she would have tried to oust the company or kept it in check through citizen oversight, with the same environmental strength and rigor she now applies to defending the waters of the Putumayo River -and all the basins, waterholes, cisterns and wetlands – particularly every time Amerisur (now Geopark) has an oil spill or one involving petroleum by products. Nearly the entire department is covered by a gray shadow of oil blocks, according to a map drawn up by Corpoamazonia in 2008. And Jani, who comes from Leticia (Amazonas) in the neighboring department where she was born, couldn't do much about getting rid of the extractive companies.

When she realized Amerisur had begun operating in the area, a lot of water had already streamed down the river: Texas Petroleum turned over its wells to Ecopetrol in 1981 and, years after a number of wells were drilled, such as Alea-1, which produced no more than 533 barrels of oil, the experiment proved to be "unattractive" for the Colombian company.

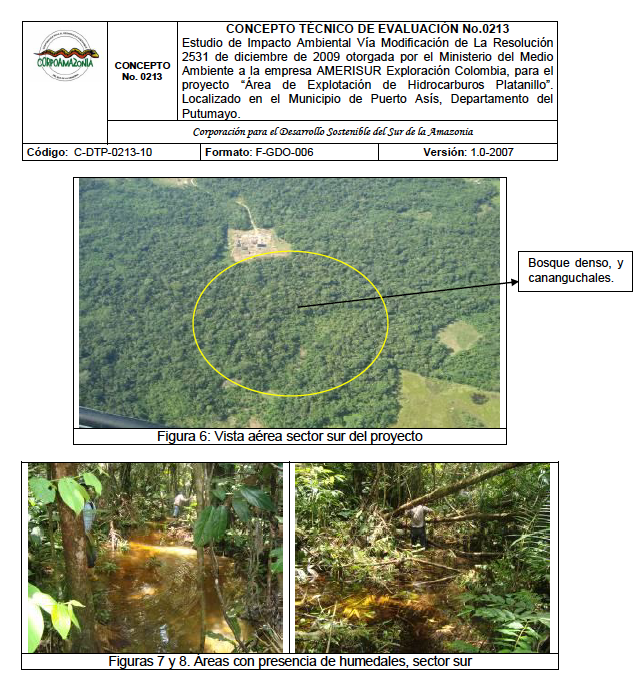

In 2004, a technical evaluation was endorsed by the National Hydrocarbon Agency (ANH), Repsol YPF and Ecopetrol to conduct exploratory operations in the Alea rural area during a period of fourteen months. So it was indicated in the environmental impact study done by Corpoamazonía in 2011, which modified Resolution 2531 granted to Amerisur in December 2009 by the Ministry of Environment Affairs at the time for its project in the so-called "Platanillo Hydrocarbon Exploitation Area".

— Our work began with those who encourage faith. It started with Father Luis and Father Alcibes. The program consisted of choosing two or three people from each rural community who were in contact with the parish and knew about the community work. We had been doing a lot, but with mingas (voluntary communal labor) and to convince the community not to knock down the banks of the streams [rivers). We started with the topic of food production. Let's suppose all the families were aware of the need to produce, but hopefully in an organic way; that they knew each and every little animal in the environment had a function, be it a worm or a fly. We started that way with the community and, later, the environmental work began with the coca problem.

When Amerisur came in, the authorities in charge of monitoring and protecting this Amazon womb, such as the National Environmental Licensing Agency (ANLA), Corpoamazonia and ANH, issue positive opinions and the necessary permits, allowing the existing blocks to operate and another 55 wells to be drilled. It was when the Piñuña Blanco and Mansoyá rivers, near the Platanillo Block, became more susceptible than ever before. The environmental warning sparked by oil production nearby, among similar operations, provided the perfect reason for establishing ADISPA. And, it was this same twist of fate that persuaded Jani to inevitably defend this underbelly of the environment at all cost.

— That was in 2007. From one moment to the next, we had to stop talking and saying our communities were Peasant Reserve Zones. In fact, our zone was no longer active, because all the leaders had to stay put, since they were going to kill us. It was when we realized the government had given up part of the PRZ in concession, and when oil production brought what is now the highway, or what they call 'the Puerto Asis-La Rosa corridor'. There are about six rural communities within that oil block, which was granted in concession.

By the end of the 1990s, several groups were operating in the Lower Putumayo region: the guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the paramilitary forces of the so-called Southern Putumayo Block, and the coca growers. At the same time, peasants like Jani Rita were marching for the right to have a PRZ; namely, a rural organization that brings them together, for example, to defend the land from an environmental perspective. According to ANZORC (an association that groups all the PRZs in the country, which are protected under Incora Resolution 0069 of December 18, 2000), peasants can "create instruments to safeguard their land against pressure from large landowners, by guaranteeing an adequate supply of services. They commit to defending and protecting natural resources".

This atmosphere in the department reached its peak with a strike by coca growers that created a very tense situation. Farmers and other residents were pleading with the governments of President Ernesto Samper and President Andrés Pastrana for options to replace crops like coca. Of course, this civil movement did not have the support of the coca growers. It was the FARC who forced them to support it, according to official documents from ADISPA.

— That was in 1996. We talked about how almost every boy or young man had a quarter of a hectare of coca. Today, that’s not worth much, but at the time having a quarter of a hectare of coca meant money, because at least they had enough to support themselves. So, from one moment to another, by around 2000, 2002 [and] 2003, you would see any boy with a quarter or half a hectare planted in coca, with money in his pocket and a rooster under his arm, going to cock fights and drinking hard liquor, beer, rum or whatever. Some even carried a gun at their waist, and not precisely because they were going to join any kind of group, but because it was part of the coca growing culture.

It was during those years that local peasants decided to organize. Just like rivers that are faithful to their course, 2,727 peasant -representing some 800 families in 23 rural parishes- came together to create the Pearl of the Amazon Peasant Reserve Zone, an area of 22,000 hectares that eventually became a border settlement across from Ecuador. This was at the start of the new millennium, between 2000 and 2001.

What awakened Jani seven years later about the oil industry was construction of the highway that starts in Puerto Asís and leads to the rural communities of Alea, La Rosa, Comandante, Sevilla, Bajo Mansoyá, Monteverde, Baldío, Peneya and Canacas. It runs for 28 kilometers alongside the Putumayo River in the same direction as the current and almost parallel to it. Although it is impossible for the parallels to touch, the road is only few meters away, coming so close it almost kisses the river, before rising for a few kilometers to follow it in the same direction.

In the 22,000 hectare reserve, Jani and her community have a 4,632 hectare headache in Alea called Amerisur. The company first applied for an environmental license in 2017, for 936 hectares, then applied for four thousand more two years later.

— We were already building the road from Puerto Asís to Alea, on our own and with pick and shovel. We did it almost entirely through volunteer communal labor (mingas). Then, when the company came in and said it was going to take over construction of the road, people relaxed. The company wanted to build it to be able to bring in tractors and everything else they were going to do to open up the platform. And, they did it from one moment to the next; it didn´t take long. With a machine, they plowed through everything that is wetland and scooped up soil from the sides to make the roadbed. If you come from Puerto Asis, there is a part where there are lakes on both sides of the road, but they are not lakes. They are the holes the company made, which filled up with water and mosquitoes as well. People complained because the holes kept them from reaching their farms from the highway, and many landowners had to build bridges to get across them.

Under Colombian law, it mandatory to consult the Ministry of the Interior if there are Indians, Afro-Colombians, other native inhabitants or Roma communities in the territories where oil is to be extracted. This must be done before a mining project can start and, of course, before the respective licenses can be granted. According to the Crudo Transparente website, since the Ministry of the Interior ignored the presence of these communities, Amerisur did not conduct prior consultations with the indigenous people who inhabit the reserves. The same applies to the peasants of La Perla Amazónica, where the Platanillo Block was established.

— We had no support from the municipal and departmental government, much less national support. Then, in a matter of days, they opened the road from Alea to La Rosa, crossing the full extent of the wetlands, after Corpoamazonia had already rejected our proposal to build the road there, saying it couldn’t be done. But with the company, Corpoamazonía ignored its earlier decision and the road was built across the entire wetland, cutting off the biological buffer that existed. We had an opportunity to visit the ecosystem with [someone from] the Environmental Attorney's Office. We even found a tapir crossing the road, and in those days a butterfly jaguar ate [a couple of] calves in the area. According to biologists, it was because the company cut through the biological buffer by building the road there.

The peasants who live in this formidable part of the country are already well aware of the direct environmental repercussions of oil exploration and production: it destabilizes the Amazon ecosystem because the oil companies dump polluting waste and deforest, which causes the soil to erode. In 2011, the National Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Colombian Amazon (OPIAC, by the Spanish acronym) complained to the authorities that Amerisur was dumping contaminated water directly into the Putumayo River and spilling oil into a stream that flows into that same waterway.

— When they first began to develop the La Rosa platform, there was a discharge hose leading directly into the Putumayo River. People suffered the consequences; they got sick. It wasn´t reported until many days later and after many people were exposed to the pollution. We realized they [the company] did not have permission to dump [waste] into the Putumayo River. Then, in more or less around 2016, they installed a pipe under the Putumayo River, by drilling a line they say passes underneath the riverbed and into Ecuador, where people also took to the streets to complain they didn’t want it there. To this day, no one knows if the company was reprimanded or what the problem was that led it to ignore environmental protocols and commitments. There are still oil spills because, when it rains, accidents happen. The water pools overflow and it is always the population that is affected by the water problem.

The Interfaith Commission for Justice and Peace accompanied these and previous complaints by asking the Office of the Comptroller General to audit "the Platanillo Block Hydrocarbon Project". However, although findings were obtained that could have led to disciplinary action, the case was shelved with the argument that "no evidence or proof of damage to the property of the nation could be found."

***

Perhaps Jani has not noticed, which might be why she did not mention it in the interview, but this year showed signs of violence in the days before President Iván Duque declared a state of emergency in March, due to the pandemic.

— No, it's horrible. At least for me, because I was shut in the first few days, not to mention the treats and persecution. Also, there was not being able to go to the farm and the fear of catching the disease. It put me in bed for almost three weeks; that’s how long it lasted.

On Saturday, February 23, at 3:15 in the afternoon, a couple disappeared from the La Playa area of Hong Kong. They were Darwin Osvaldo Reyes and Rocío Milena García, farmers from the La Perla Amazónica PRZ, which is headed by Jani Rita. They were enrolled in the Illicit Crop Substitution Program (PNIS) and had been seen that day at the Farmers Bank collecting money they had been paid through the Immediate Assistance Plan (PAI, by the Spanish acronym). They also were victims of forced displacement, due to events that occurred in the region during 2013. The search for the couple began four days later, and their bodies were found in the Putumayo River. According to ADISPA, all of this information was reported to the municipal attorney.

Item 4 in the Peace Accords signed by the previous government and the FARC calls for the substitution of illicit crops. However, due to insufficient incentives and lack of compliance in that respect, some peasants went back to growing coca. The quarantine in Colombia had not been lifted when, on June 30, soldiers from the 27th Jungle Brigade arrived in San Salvador, a village in Sector 2 of La Perla Amazónica, to eradicate the coca being grown there.

— People say they are willing to defend the few plants they have because, compared to what was there before, now there is nothing. What the government did was simply hand out twelve million pesos and not to all the families. And, the authorities think it was enough. So, people pulled up the bushes (coca), since they had those twelve million pesos, and now there is another assortment of needs. It's not the fault of the peasants that they got involved in this eradication program and the government didn't comply.

Now, with coca crop substitution, Jani believes the series of recent disappearances and murders might be related to it. So are the threats.

— We also know it is not in the best interest of groups that come in to find the farmers organized and wanting descent living conditions. We want to look at other options for crops. This is a question about which nothing is known. It is the responsibility of the Prosecutor's Office, which has not made any sort of inquiries regarding the investigations. In the last two years, there have been no threats. There have been searches. They have come to my house. I’ve had to flee the farm, and I have been persecuted here at my home in Puerto Asís.

The small building where ADISPA and the La Perla Amazónica PRZ meet is located near the Putumayo River, in a green field that shines in the sunlight. To deal with the pandemic, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) donated facemasks for them to use, and the Interfaith Commission that accompanies them in their environmental work provided a supply of quaternary ammonium disinfectant for the peasants to fumigate their houses.

— This virus makes the work more difficult and less productive, because more effort is needed but fewer people are being reached. I tell you, this week and last week we went almost house by house to see the children who are in the program that is adopting trees. And, today, we had a rather large meeting, with about eighteen people. However, since we have a fairly big building, we can apply the biosafety protocol. Each one is given a mask, and before any meeting on anything, the boys have to teach the biosafety protocols, taking ten minutes to generate an awareness of care.

Jani doesn't stop. Just like the Putumayo River and the Amazon womb, she and her people never stop moving and caring for life.

Comentar